On every dollar, the US government used to print “Redeemable in gold on demand from the US Treasury,” a statement of confidence that the US certifies its liabilities in gold. Nowadays, a dollar can only be redeemed for another dollar from the government–pretty confusing. While the current dollar is not backed by anything, from 1959 to 1973, gold backed the dollar. In the gold exchange standard, the world’s governments attempted to preserve stable exchange rates–often at the expense of domestic economic growth. Ultimately, the adjustments to governments’ economies and political effects were too costly, and the Bretton Woods system collapsed into a floating exchange rate system. The Bretton Woods system reveals the interesting nature of the gold exchange rate system, and its fall displays how governments weigh the trade-off between stable exchange rates and domestic economic autonomy.

The Bretton Woods system is highly different compared to the contemporary regime. Today’s system uses floating exchange rates, which are dictated by the supply and demand of private actors. The Bretton Woods system used fixed exchange rates, where all cooperating countries pegged their exchange rates at constant values.

The Bretton Woods system’s primary reserve asset was the US dollar, which could be converted into one ounce of gold for $35. The world’s confidence in the US government’s ability to convert dollars into gold underlined the system. Most industrialized countries then pegged their currency based on the dollar. These different currency values in gold values generated the exchange rates of the system.

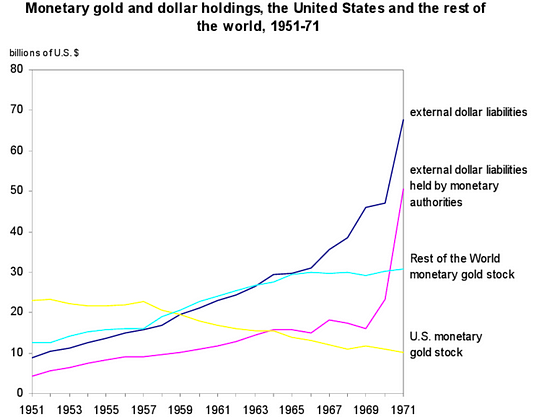

By the middle of the 1960s, cracks were showing in the Bretton Woods system. Most notably, international claims on US dollars were larger than US gold reserves. This dollar overhang was very destabilizing as the US did not have the resources to fulfill its international obligations. Confidence in the dollar faltered, and speculative attacks commenced against it.

As the world used the dollar as its primary reserve asset, the growth of dollars circulating in the international economy needed to equal the expansion rate of world trade. However, as the foreign dollar supply grew, the dollar overhang expanded, causing more suspicion about the safety of the dollar.

To reduce the dollar overhang, the US needed to import more dollars than it exported–to produce consistent balance-of-payment surpluses. However, reducing dollars in the international economy could create liquidity problems for the global trade system. The Bretton Woods system faced a dilemma. The US could either increase international dollar reserves, ultimately succumbing to a run on the dollar, or the US could generate balance-of-payments surpluses, producing liquidity problems for international trade that may culminate into crises.

International efforts attempted to resolve the issue by resolving payment imbalances. The US claimed that payment-surplus countries like Germany and Japan caused the US imbalance and that they needed to support the dollar in foreign exchange markets. Surplus-generating companies initially assisted the US by refusing to convert dollars to gold or purchase dollars in foreign exchange markets. In Germany, the government agreed to forgo converting dollars to gold and scheduled “offset payments” that helped ease the payment imbalance.

Eventually, the commitment of the international community was worn out. As Germany protected the dollar, their economy began facing high inflation. Purchases of dollars for German marks caused the German money supply to expand. Due to the historical stigma of the 1923 hyperinflation, the German government could no longer support the dollar and expect to remain in office.

The US government had two other options to protect the Bretton Woods system: either devalue the dollar or produce adjustments through economic contraction. The US did not believe they could successfully devalue the dollar as other countries could devalue in proportion to the US. Meanwhile, President Richard M. Nixon, who became president in 1969, was unwilling to adopt policies of economic contraction to eliminate the deficit.

President Nixon was concerned about his reelection prospects if he attempted to deflate the US economy. Even though economic contraction was needed to preserve the Bretton Woods system, President Nixon decided that reducing unemployment would be his administration’s primary macroeconomic objective. Both US fiscal and monetary policy became expansionary in the lead-up to the 1972 Presidential Election. President Nixon increased government spending and requested that the Federal Reserve increase the money supply (it is highly possible the Fed simply expanded in coincidence with Nixon’s wishes).

In reducing unemployment, President Nixon sacrificed the Bretton Woods system. Increased domestic demand expanded the current account deficit, while lowered interest rates caused capital outflows. The culmination of a larger trade deficit and lower capital account exacerbated the payment imbalance. Speculative attacks on the dollar accelerated. In May 1971, Germany had to purchase $2 billion in two days, a record at the time. The economic commitment exceeded the German willingness to defend the dollar, and the government responded by floating the mark.

Facing reelection pressures, Nixon suspended the dollar’s convertibility into gold in August 1971. Governments attempted to save the Bretton Woods system one final time through a currency realignment; however, the recovery could not resolve the system’s fundamental issues. The US was unwilling to lower its payment deficit, and Germany would not commit to increased inflation. By the beginning of 1973, the Bretton Woods system fell.

The fall of the Bretton Woods system reveals many essential aspects of the international monetary system and its actors. Governments cannot achieve both stable exchange rates and domestic economic autonomy. There is a macroeconomic trade-off that governments face. A government must sacrifice domestic economic autonomy to achieve stable exchange rates, which are important for international trade. Governments must be willing to endure recessions and inflation to preserve the international monetary order. The fall of the Bretton Woods system shows how difficult these commitments can be. The US was unwilling to incur the costs of reducing its payments deficit, and Germany could not bear the inflation caused by defending the dollar. Without a solution that guarantees stable exchange rates and domestic economic autonomy, governments must choose between the two.

The US and German governments could not expect to be reelected if they sacrificed their economies for fixed exchange rates. In democratic systems, domestic economy autonomy is very important to voters. For a democratic politician to stay in office, they must prioritize domestic economic autonomy to stable exchange rates. As governments began floating their exchange rates in 1973, they could now control the pace of their economies to the satisfaction of their voters. Nevertheless, this new age of floating rates produced a new kind of fragility through unstable global capital flows.